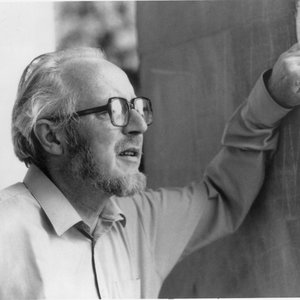

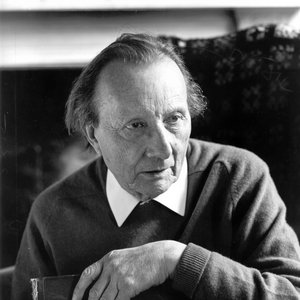

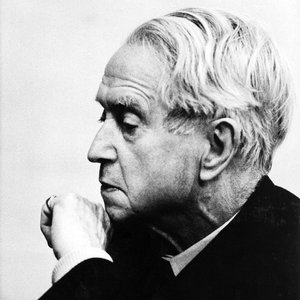

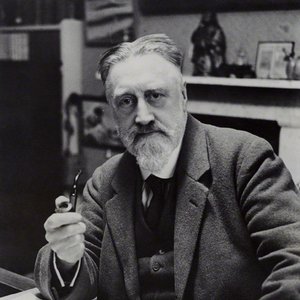

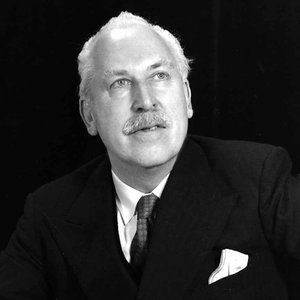

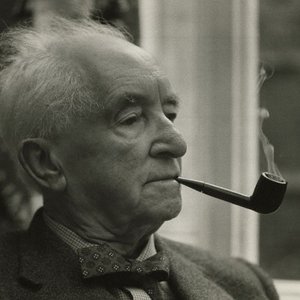

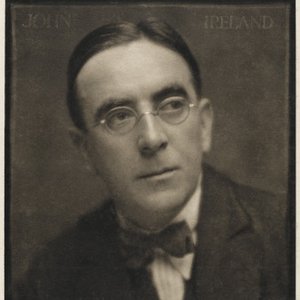

Biography

-

Born

23 May 1901

-

Born In

Northampton, Northamptonshire, England, United Kingdom

-

Died

14 February 1986 (aged 84)

Edmund Rubbra (23 May 1901–14 February 1986) was a British composer. He composed both instrumental and vocal works for soloists, chamber groups and full choruses and orchestras. He was highly respected by fellow musicians and was at the peak of his public popularity in the mid-20th century. The most famous of his works are his eleven symphonies. Although he was composing at a time when many people wrote twelve-tone music, he decided not to compose in this style. Instead he devised his own distinctive method of composition. His later works were less popular with the concert-going public, although he never lost the respect of his fellow-professionals. His music is, therefore, less well-known today than would have been expected from his early popularity. His compositions are full of drama, with an improvisatory feel.

Edmund Rubbra was born in Northampton. His parents encouraged him in his music, but they were not professional musicians, though his mother had a good voice and sang in the church choir, and his father played the piano a little, by ear. Rubbra’s artistic and sensitive nature were apparent from early on. He remembered waking one winter’s morning when he was about three or four years old, and noticing something different about the light in his bedroom; there was light where there was usually shadow, and vice versa. When his father came into the room, Edmund asked him why this was. His father explained that there had been a fall of snow during the night, and so the sunlight was reflecting off the snow and entering Edmund’s bedroom from below, instead of above, thus reversing the patterns of light and shade. When Rubbra was much older he came to realize that this ‘topsy-turveydom’, as he called it, had caused him to often use short pieces of melody which would sound good, both in their original form and when inverted (so that when the original melody goes up a certain amount, the inverted one goes down the same amount). He then set these two melodies together, but slightly offset from one another, so that the listener hears the melody going up, say, then an echo where it goes down instead.

Another childhood memory which Rubbra identified as later affecting his music, took place when he was nine or ten. He was out walking with his father on a hot summer Sunday. As they rested by a gate, looking down at Northampton, he heard distant bells, ‘whose music seemed suspended in the still air’, as he put it. He was lost in the magic of the moment, losing all sense of the scenery round about him, just being aware of (and I quote his own words) ‘downward drifting sounds that seemed isolated from everything else around’. He traces the ‘downward scales that constantly act as focal points in textures’ to this experience.

Rubbra took piano lessons from a local lady with a good reputation and a piano with discoloured ivory keys. This instrument contrasted starkly with the piano on which Rubbra practised, which was a new demonstration upright piano, lent to his family by his uncle by marriage. This uncle owned a piano and music shop, and prospective buyers would come to Rubbra’s house, where he would demonstrate the quality of the piano by playing Mozart’s Sonata in C to them. If the sale went through, the Rubbra family was given commission, and a new demonstration piano took the place of the sold one.

In 1912, Rubbra and his family moved to the centre of Northampton, moving again four years later so that his father could start his own business selling and repairing clocks and watches. At this house, above the shop, Edmund had the back bedroom for his work, but the stairs were not wide enough to allow the piano to be brought up, so the window frame of his room had to be removed in order to get the piano in from outside.

Rubbra started composing while he was still at school. One of his masters, Mr. Grant, asked him to compose a school hymn. He would have been very familiar with hymn tunes, as he attended a Congregational church and played the piano for the Sunday School. He also worked as an errand boy whilst he was still at school, giving some of his earnings to his parents to help with their finances.

At the age of 14, he left school and started work in the office of Crockett and Jones, one of Northampton’s many boot and shoe manufacturers. Edmund was delighted able to accrue a number of stamps from parcels and letters sent to this factory, as stamp-collecting was one of his hobbies. Later, Rubbra was invited by an uncle, who owned another boot and shoe factory, to come and work for him. The idea was that he would work up from the bottom of the company, with a view to ownership when his uncle, who had no sons of his own, died. Edmund, influenced by his mother’s lack of enthusiasm for the idea, decided to decline. Instead, he took a job as a correspondence clerk in a railway station. In his last year at school he had learned shorthand, which was an ideal qualification for this post. He also continued to study harmony, counterpoint, piano and organ, working at these things daily, before and after his clerk’s job.

Rubbra’s early forays into chamber music composition included a violin and piano sonata for himself and his friend, Bertram Ablethorpe, and a piece for an excellent local string quartet. He used to meet with the keen, young composer, William Alwyn, who was also from Northampton, to compare notes.

Rubbra was deeply affected by a sermon he heard given by a Chinese Christian missionary, Kuanglin Pao. He was inspired to write Chinese Impressions — a set of piano pieces, which he dedicated to the preacher. This was the beginning of a lifelong interest in things eastern.

At the age of 17, Rubbra decided to give a whole concert of Cyril Scott’s music in the Carnegie Hall, in Northampton Library. This proved to be a very important decision, which would change his life. The minister from Rubbra’s church attended the concert and, secretly sent a copy of the programme to Cyril Scott. The upshot of this was that Scott took Rubbra on as a pupil. Working in the railway office was fortunate, because one of the perks of the job was cheap rail travel, so Rubbra was able to get to Scott’s house by train, paying only a quarter of the usual fare! After a year or so, Rubbra gained a scholarship to University College, Reading. Gustav Holst became one of his teachers here. Both Scott and Holst had an interest in eastern philosophy and religion, inspiring further interest in the subject from Edmund.

Holst also taught at the Royal College of Music and advised Rubbra to apply for an open scholarship there. His advice was followed and the place was secured. Before Rubbra’s last term at the Royal College, he was unexpectedly invited to play the piano for the Arts League of Service Travelling Theatre on a 6 week tour of Yorkshire, since their usual pianist had been taken ill. He accepted this offer despite it meaning he missed his last term. This provided him with invaluable experience in playing and composing theatre music, that he never regretted and stood him in good stead for his later dramatic work. In the mid-1920s Rubbra used to earn money playing for dancers from the Diaghilev Ballet. At around this time he became firm friends with Gerald Finzi.

In 1933, Rubbra was married to Antoinette Chaplin, a French violinist. They toured Italy together, as well as giving recitals in Paris and radio broadcasts. They had two sons, Francis and Benedict, with the marriage lasting into the late 50s. Later, Rubbra married Colette Yardley, with who he had one son called Adrian.

During the Second World War, in 1941, Rubbra was called up for army service. After 18 months he was given an office post, again on account of his knowledge of shorthand. While he was here, he ran a small orchestra assisted by a double-bass player from the BBC orchestra. The War Office asked him to form a piano trio to play serious music to the troops. Rubbra was happy to oblige, and the trio, “The Army Classical Music Group”, was formed. Rubbra, playing the piano, was joined by William Pleeth (cello) and Joshua Glazier (violin). They travelled all over England and Scotland and then to Germany, with their own grand piano which, with its legs removed for transport, became a seat for them in the back of the transport lorry!

After the war, in about 1947, Rubbra became a Roman Catholic, writing a special mass in celebration. Also at this time, the University of Oxford were forming a faculty of music. They invited Rubbra to be a lecturer there. After much thought, he accepted the post. The army trio kept meeting, playing at clubs and broadcasting, for a number of years, but eventually Rubbra was too busy to continue with it.

It is a measure of the high esteem in which Rubbra was held in the 1940s, that his Sinfonia Concertante and his song Morning Watch were played alongside such works as Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius, Kodaly’s Missa Brevis and Vaughan Williams’s Job, at the 1948 Three Choirs Festival.

When Vaughan Williams heard that the University of Durham was going to confer an Honorary D.Mus on Rubbra in 1949, he wrote him a very short letter. ‘I am delighted to hear of the honour which Durham University is conferring on itself’.

Another sign of Rubbra’s significance is evident in his receiving a request from the BBC to write something for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. The result was Ode to the Queen, a piece for voice and orchestra, to Elizabethan words.

On Rubbra’s retirement from Oxford, in 1968, he did not stop working, he merely took up more teaching at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. Neither did he stop composing. Indeed, he kept up this activity right until the end of his life. He had, in fact, started a 12th Symphony in March, 1985, less than a year before his death.

Ronald Stevenson summed up the style of Rubbra’s work rather succinctly when he wrote, “In an age of fragmentation, Rubbra stands (with a few others) as a composer of a music of oneness”.

Sir Adrian Boult commended Rubbra’s work by saying “He…has never made any effort to popularize anything he has done, but he goes on creating masterpieces”.

Artist descriptions on Last.fm are editable by everyone. Feel free to contribute!

All user-contributed text on this page is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply.